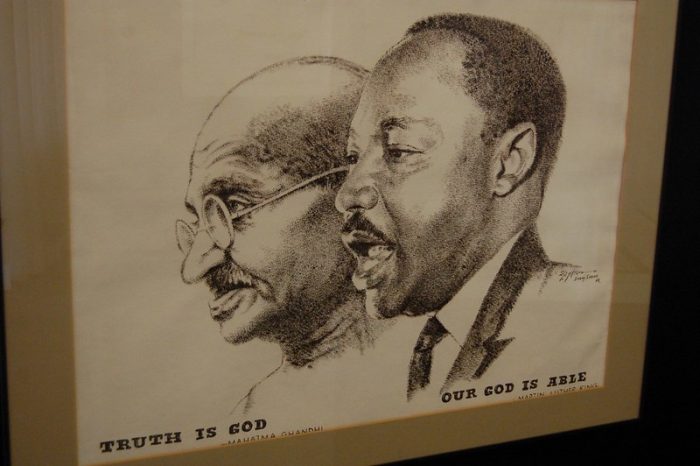

In moments of protest and resistance, particularly when led by Black and Indigenous communities and other people of color (BIPOC), white people often respond by invoking figures like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. or Mahatma Gandhi to promote ideals of nonviolence.

On the surface, these invocations may appear to be appeals to peace, unity, or moral high ground. But in practice, they are often weaponized to silence legitimate rage, sanitize the discomfort of white audiences, and strip oppressed people of their full humanity and agency.

Rather than being expressions of solidarity, these gestures often perpetuate a more insidious form of violence—one that cloaks itself in moral superiority while reinforcing the very systems of domination being protested.

Historical Erasure and Sanitization

The most glaring issue is that these historical figures are almost always presented in oversimplified, decontextualized ways. Dr. King, in particular, has been so thoroughly sanitized in mainstream white discourse that his legacy is often reduced to the “I Have a Dream” speech, completely divorced from his fierce critiques of capitalism, white moderates, militarism, and systemic racism.

The King who said “a riot is the language of the unheard” is rarely quoted. The King who denounced the Vietnam War and described the United States as “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world” is systematically erased.

Similarly, Gandhi is often cited for his doctrine of satyagraha, or nonviolent resistance, but this too is misrepresented. Gandhi’s relationship with Black South Africans during his early years in South Africa was deeply problematic, and his views on race evolved in ways that are still contested. He lived and fought in colonial contexts vastly different from those faced by modern Black Americans confronting police violence or Palestinians resisting military occupation.

When white individuals selectively invoke these figures, they ignore the broader context of their resistance and the specific systems of oppression they were fighting against. More importantly, they erase the vast diversity of resistance strategies used by oppressed peoples throughout history, many of which have included armed self-defense, community protection, and direct confrontation of power.

Moral Policing as Violence

The invocation of King or Gandhi becomes a form of moral policing—an effort to define the boundaries of acceptable resistance according to white comfort. This moral policing is itself a form of violence. It demands that people respond to systemic brutality with docility. It equates property damage with bodily harm. It conflates righteous anger with hatred.

And it demands that those being actively dehumanized do the emotional labor of comforting their oppressors.

To tell a grieving, outraged community that they must be peaceful and calm in the face of violence is to gaslight them. It is to deny the real pain, generational trauma, and existential threat they face. It suggests that the oppressed must earn their humanity through perfection, while those in power are allowed to maintain their violence unchallenged.

Who Benefits from “Nonviolence”?

When white people invoke nonviolence, they are often less concerned with the safety of the protestors than with the preservation of order, particularly the racial and economic status quo. These calls for calm rarely come with calls to dismantle the systems that make resistance necessary in the first place. They are not accompanied by demands to defund police forces, end military occupations, or hold governments accountable for atrocities. Instead, they become a tool to delegitimize protest, to focus media attention on “violence” by protestors rather than the structural violence that prompted protest in the first place.

Nonviolence is not inherently passive or submissive—it can be radically disruptive. But when it is only invoked in response to unrest by BIPOC communities, and not to critique state violence or structural injustice, it becomes a weapon of control. A silencer. A leash.

Respectability Politics and the Illusion of Safety

The insistence on nonviolence is often tied to respectability politics, the belief that if BIPOC individuals just protest “the right way,” then they will finally be heard, respected, or granted justice. But this myth has been disproven time and again. Dr. King was assassinated. Malcolm X was assassinated. Fred Hampton was assassinated. Peaceful protestors have been beaten, gassed, and jailed. Kneeling football players are blackballed.

The issue has never been the method of protest—it has always been who is protesting and what they are challenging.

The idea that oppressed people must behave a certain way to earn empathy is deeply dehumanizing. It implies that their pain must be pre-packaged into something palatable for those in power to consider it worthy of attention. It reinforces a world where Black lives only matter when they die quietly, without disruption.

The Right to Rage

Anger is not the opposite of peace. In fact, anger is often a prerequisite for justice. It is an appropriate, necessary response to centuries of brutality, erasure, and exploitation. To deny people of color their right to rage is to deny them their full personhood. It is to demand their submission in the face of tyranny.

If white people truly want to honor the legacy of Dr. King or Gandhi, they must confront their own complicity in systems of oppression, listen more than they speak, and allow space for resistance that makes them uncomfortable. True solidarity requires surrendering the need to control the narrative and letting oppressed communities lead, even when their methods challenge norms, disrupt peace, and shatter illusions.

Holding up Dr. King and Gandhi as moral yardsticks to shame modern-day protestors is not a gesture of peace—it is an act of erasure, control, and violence. It silences the voices of those who are fighting for their lives, and turns liberation struggles into morality plays for white audiences. It is time to disarm this weapon of comparison and instead ask: What are we doing to dismantle the systems that make resistance necessary in the first place?

Until white people can answer that question honestly, invoking King or Gandhi is not solidarity—it is complicity.

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply