I am not a poet. Far from it.

But yesterday, while organizing some of my essays—some finished, others still rough—I came across a poem I had started during my dad’s decline, sometime after his first stroke at age eighty-eight.

At the time, I was struggling with how everyone—myself included—seemed to be focusing on the “Getting-Really-Old-and-Declining Dad.”

The dad with his back bending lower, day by day, as though time itself was tugging him downward.

The dad who shuffled so slowly behind his walker we were convinced he might be moving in reverse.

The dad who told meandering stories that even AI would get lost trying to follow.

But that wasn’t all of him.

Aside from scoliosis and a heart arrhythmia he’d had since childhood, my dad had enjoyed remarkably good health most of his life. And last summer, determined to prove he still had strength, he walked slowly—without the walker—around our kitchen island.

Hand on the counter for balance, he moved with focus. Then, standing still, he let go and looked at each of us.

See? I can stand here! No walker!

It was one of those moments: Dad as Dad. Resilient. Proud. Wanting to be seen not for what he’d lost, but for what still remained.

Just a few months later—November 2024—a second stroke took nearly everything. He couldn’t walk. He couldn’t feed himself. His speech was limited, though he could still say “I love you” in a voice that sounded more like Scooby-Doo than himself. We moved him into hospice at a nursing home.

We said goodbye more than once.

My husband called him the comeback kid—for good reason.

In early April, he got COVID and—somehow—bounced back again. At ninety-one.

But on April 16, 2025, as I was on my way to visit him, I got the call. This time, it really was goodbye.

I hadn’t planned to do anything with that poem. But there it was.

I opened it. Sat with it. Let my heart crack open again.

And this is what came out:

He Was Not His Final Days

He was not his final days—

not the hospital bed,

not the silence between breaths,

not the fading light in his eyes.

He had more time behind him

than ahead,

the line between life and loss

moving in pauses and returns.

His memories blurred.

The present loosened its grip.

He spoke in fragments,

wandered through time.

Mostly,

he was at Pine Lake—

where towering pines stood watch,

and the dock stretched into still water.

Where he spent boyhood summers,

then built a cottage

for us.

There,

he was whole.

And even as his body failed,

his spirit returned

to the trees he knew by name.

We met him there—

in the place his mind had gone.

Walked his pace,

nodded at his meandering stories,

loved him as he was.

We thought he could linger for years—

caught between here and there.

But then,

the leaving began.

It was not peaceful.

Not like the lake—

no hush of trees,

no stillness.

His breath was ragged.

His body fought.

I stroked his hair.

Told him he was loved.

Told him to go to the lake.

Beside his bed

hung a painting of Pine Lake—

not the full sweep,

just dense trees in quiet shade,

and a glimpse of water.

In his final moments,

his cloudy eyes found it.

Then found me.

And he was gone.

He was not his final days.

He was the man before them—

the quiet laugh,

the hands that could do anything,

the trees that knew him.

He was Pine Lake.

Pine Lake was his place. It had become mine too.

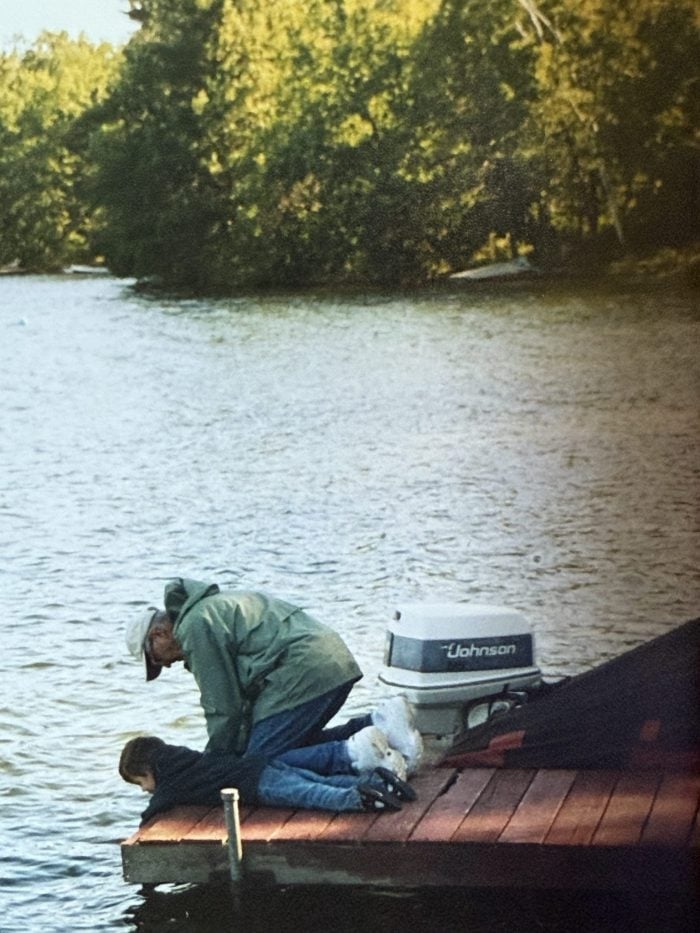

He spent his boyhood summers there, and later built a cottage for our family.

It’s the Happy Place I return to in my mind when I need peace.

We haven’t been back in many years, but I can still picture the pier, hear the lullaby of loons. It was where time slowed down.

No TV. Just stacks of books, card games, days spent swimming, or walking the narrow, winding dirt road.

It’s more complicated now. The lake is still beautiful. Still quiet.

But now, it holds him too. And I’m learning how to carry that.

The painting that once hung in my parents’ home—before taking up residence beside my dad’s nursing home bed—now hangs in my office.

It was painted by Richard Schmid, my dad’s childhood friend, who once visited the lake with him and went on to become a well-known artist.

It’s just trees and water.

But I know it’s Pine Lake. I look at it every day.

And I think my dad would quietly nod at this.

Feel it all. Maybe even smile.

I would love to hear from you if this resonates with you in any way.

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 2 comments and reply